Vernon Fisher

Dark Waves Rising

Talley Dunn Gallery

October 25 – December 1, 2019

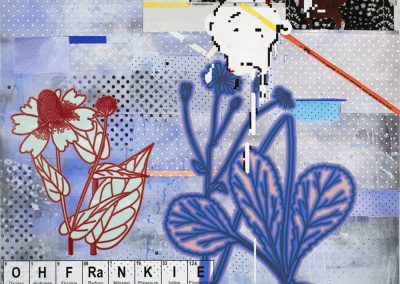

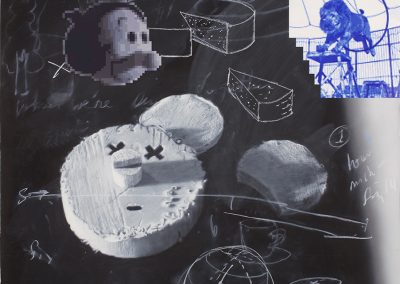

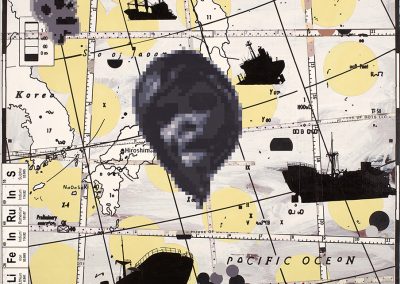

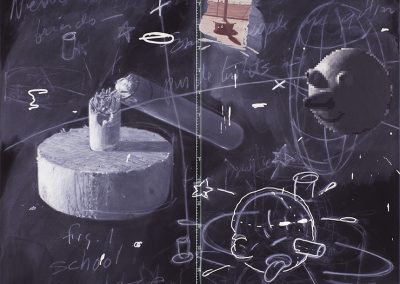

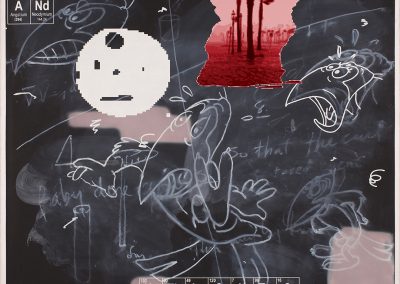

Dark Waves Rising features paintings, works on paper, and mixed media works by Vernon Fisher that appropriate visual vocabulary from sources as scholastic as illustrations in science textbooks to famed early twentieth-century cartoons. In dialogue with postmodern theorists, Fisher uses a wide range of media to create large-scale collages and paintings that evince complex visual narratives. His hallmark blackboard paintings employ a slate-gray background and smudged scribbles, effectively replicating a chalkboard’s layered patina. The blackboard’s association with both science labs and childhood classrooms adds an acute depth to the representational fragments, erased texts, and symbols within the artist’s paintings. However, Fisher is careful to ensure that for all of the loaded imagery in his works, the completed artworks ultimately elude cohesion. Abstraction in Fisher’s art across mediums facilitates attempts at making sense of our increasingly complicated world without any guarantees of success.

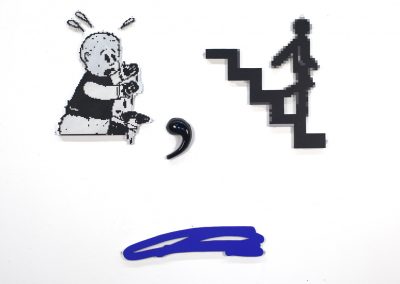

Titled after the ending of a story Fisher recently wrote, Dark Waves Rising presents a body of work that encapsulates the development of the artist’s process and concerns. Fisher has long been deeply invested in contradiction’s ability to reveal especially when it leads to the indecipherably ominous. One of the earlier works in the exhibition, Descent of Man, illustrates how one might approach Fisher’s oeuvre. At first glance, the components of the work are immediately intelligible—an emphatically sweating cartoon figure that has been digitized, a sculptural comma, a generic pixelated icon of a person walking down steps. However, these images do not remain static. When one considers the gestural swath of blue underneath the other pieces, the composition morphs into a face. The blue scrawl suggests a mouth, transforming the comma into a nose and the figures into eyes. Furthermore, the title makes art historical reference to Duchamp and evokes Charles Darwin’s theory of human evolution. Working to build layers of ironic indirection, Fisher’s compositions vacillate between the micro and macro levels.

In navigating the disparate images and cultural citations that collide with one another on Fisher’s picture planes, viewers feel the calamity present on the faces of his figures. Fisher invites viewers into intentionally cacophonous spaces, explaining, “Scientists prefer a high signal to noise ratio, but for me, the noise is part of the picture, and to leave it out would be dishonest. Besides, noise is interesting.”