Erick Swenson

Talley Dunn Gallery

January 21 – March 11, 2017

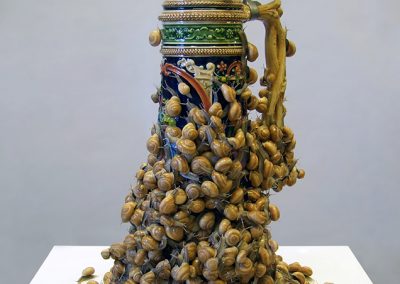

This exhibition will highlight three sculptures by Swenson from the recent past, Ne Plus Ultra, Study for Dressage, and Schwamerei. These three works along with other sculpture by Swenson from museum and private collections will soon be traveling to the Honolulu Museum of Art for Swenson’s mid-career museum survey. Often taking years to complete, each of Swenson’s sculptures is meticulously rendered through complex processes of painting and sculpting. Painstakingly created over a period of more than a year, Ne Plus Ultra presents a fallen deer lying on its side and displayed in a state of decomposition as it lays on a low, wide plinth. All of Swenson’s incredible detail pulls the viewer closer to appreciate the mass of the form and the meticulous scrimshaw carving featured on its bones, leaving the viewer to experience a range of emotion, from disgust to awe and perhaps eventual appreciation. Swenson formed the work by casting each part piece by piece in polyurethane resin before painting and assembling the tableau. The scrimshaw maps highlighted on the bones of the deer were made with a sand etching machine and then carefully painted with acrylic.

As with many of the artist’s earlier sculptures, the fallen deer presented in Ne Plus Ultra (of which one from the edition is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston) serves as a surrogate for the human figure to create a compelling, open-ended narrative that brings to mind significant issues of vulnerability, loss, and our eventual mortality. Ne Plus Ultra relates to Swenson’s important earlier pieces that also feature the deer figure, including Untitled from 2000 with a young deer balancing on one hoof with a black and red drapery billowing above its head (in the permanent collection of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth) and Untitled, 2001, with an adolescent deer rubbing the velvet off of its newly developed horns on an antique rug (exhibited in the Whitney Biennial in 2004).

Moreover, Ne Plus Ultra (meaning “nothing beyond this”) shows a curious take on the memento mori tradition, as the sculpture’s title references not only our sense of the unknown after death, but also the limits to our experience and knowledge of the world around us. The words ne plus ultra were written on maps in the 15th and 16th centuries to label areas that were unknown or unexplored. The scrimshaw carving upon the bones offers nautical maps both real and imaginary, alluding to a common 19th century practice of engraving sea routes and sailors’ adages onto the bones of sea mammals.

Once the viewer acknowledges the grisly details of the deer’s rotted flesh, he/she is able to see the delicate engraving of the scrimshaw maps to etched on the bones. The secret of the animal’s hidden destiny is revealed only after it has died and has begun to disintegrate. In essence, Swenson’s sculpture suggests that by confronting the unknown or acknowledging our own mortality, we are perhaps able to discover the underlying purpose and meaning of our lives.